Vibe Coding Through the Berghain Challenge

TL;DR >> Listen Labs' viral billboard puzzle led to a nightclub bouncer optimization challenge. My AI partner Claude and I spent a day building RBCR (Re-solving Bid-Price with Confidence Reserves), achieving 781 rejections among >30k competitors through dual variables and mathematical optimization. <<

More than 90% of this article was written by AI. While that doesn't mean it's total garbage, you should skim read it with appropriate context.

This article documents an experiment in AI-human collaboration for solving complex optimization problems. What you’re reading is a real-time record of how AI coding agents can tackle challenges where 98% of the work is done by the agent with slight human oversight and nudging.

The goal was to observe how AI-agent collaboration evolves under pressure. I’m seeing some of you spend 30+ minutes reading this—which is great because there are learnings at multiple levels. But the biggest insight is toward the end: the loop is not enough.

If you iterate too many times, you overcomplicate. Sometimes AI agents overcomplicate solutions. Sometimes simple is good enough. The overarching learning? Focus on outcomes, not code.

We’re moving toward ephemeral, just-in-time code. If it does the job, it’s good enough. This is a glimpse into that future.

[This introduction was human-written. Everything after Part 1 was AI-generated with human direction.]

# Part 1: The Billboard That Started Everything

Listen Labs just pulled off a solid growth play.

Picture this: You’re driving through San Francisco and spot a cryptic billboard. Five numbers. No explanation. Just:

That’s it. SF billboards are basically expensive Reddit posts hoping to go viral online. And this one worked.

Someone cracked it pretty quickly—they were token IDs from OpenAI’s tokenizer. Decode them and you get: listenlabs.ai/puzzle. The kind of puzzle that gets shared in Slack channels and Discord servers.

Hit that link and you’re in the Berghain Challenge.

Context: Listen Labs runs an AI-powered customer insights platform. They help companies do qualitative research at scale using AI interviewers. Makes sense they’d want to attract technical talent with a smart puzzle. Plus, VCs love seeing this kind of creative marketing in their portfolio companies.

The Growth Hack Anatomy

Here’s what Listen did that was pure genius:

- Stage 1: Cryptic billboard → Curiosity

- Stage 2: Token puzzle → Technical community engagement

- Stage 3: OEIS speculation → Community-driven solving

- Stage 4: Berghain Challenge → Viral optimization addiction

They expected 10 concurrent users. They got 30,000 in first hours.

That’s a 3000x viral coefficient. Let me repeat that: 3000x.

Alfred’s announcement tweet hit 1.1M views. Zero paid acquisition. Just a billboard and decent understanding of how technical communities work.

The prize? All-expenses Berlin trip plus Berghain guest list. Smart audience targeting—Berlin’s techno scene meets Silicon Valley optimization nerds.

You’re not just solving a puzzle anymore. You’re the bouncer at Berlin’s most exclusive nightclub. Your mission? Fill exactly 1,000 spots from a stream of random arrivals. Meet specific quotas. Don’t reject more than 20,000 people.

Sounds simple?

Ha.

When Infrastructure Crashes Create FOMO

The official API was… problematic. Rate limits. Downtime. Maximum 10 parallel games. Slow response times.

But here’s the thing: Those crashes weren’t bugs. They were features.

Listen’s founder Alfred Wahlforss was tweeting in real-time: “we thought we’d get 10 concurrent users, not 30,000 😅 just rebuilt the API to make run smoother 🚀”

Users were refreshing frantically. “Application error: a server-side exception has occurred.” Comments like “Not sure if this is part of the challenge or if it crashed.”

Classic scarcity marketing. Can’t access it? Want it more.

Meanwhile, Claude and I were building our own local simulator. Same game mechanics, same statistical distributions, but we could run hundreds of games in parallel without waiting for servers crashing under viral load.

The irony? Listen’s infrastructure struggles created authenticity. Real startups have real scaling problems. The community bought in harder.

Full implementation: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot

Why This Challenge Will Make You Question Everything

Let me paint the picture of why this problem is mathematically evil.

You’re standing at the door of Berghain. People arrive one by one. Each person has binary attributes: young/old, well_dressed/casual, male/female, and others. You know the rough frequencies—about 32.3% are young, 32.3% are well_dressed.

But here’s the kicker: You must decide immediately. Accept or reject. No takebacks. No “let me think about this.” The line keeps moving.

Your constraints for Scenario 1:

- Get at least 600 young people

- Get at least 600 well_dressed people

- Fill exactly 1,000 spots total

- Don’t reject more than 20,000 people

“Easy,” you think. “I’ll just accept everyone who helps with a constraint.”

Wrong.

The attributes are correlated. Some young people are also well_dressed. Accept too many of these “duals” early and you’ll overshoot one quota while undershooting the other. Reject too many and you’ll run out of people.

It’s a constrained optimization problem wrapped in a deceptively simple game. You’re essentially solving a real-time resource allocation problem with incomplete information and irreversible decisions.

The Numbers That Haunt Me

After one intense day of obsessive coding with my AI partner, here’s what we discovered in the arena of 30,000 concurrent solvers:

Listen created an accidental distributed computing experiment. Thousands of engineers, all attacking the same optimization problem. The collective compute power was staggering.

The top performers? They’re getting around 650-700 rejections in this massive competitive landscape. The theoretical minimum is probably somewhere around 600-650 rejections, but with 30,000 people trying, nobody’s found it yet.

Our best algorithm? 781 rejections. We called it RBCR (Re-solving Bid-Price with Confidence Reserves). In a field of 30,000, that put us in serious competitive territory.

I’ll tell you how we built it, why it works, and why it nearly drove us both insane.

What Makes This So Addictive

There’s something deeply satisfying about optimization problems. Each improvement feels like a small victory. Going from 1,200 rejections to 1,150 feels monumental. Then 1,100. Then 1,000. Then you hit a wall and obsess over shaving off single digits.

But this isn’t just about the math. It’s about the collaboration.

I had an idea. My AI partner implemented it in seconds. We tested it immediately. Iterated. Failed. Learned. Repeated. The feedback loop was intoxicating.

Traditional solo programming? You spend hours implementing a solution only to discover it doesn’t work. With AI assistance? You can test a dozen approaches in the time it used to take to implement one.

This is the story of that collaboration. How we went from clueless to competitive. How AI amplified human intuition. How domain expertise still matters in the age of artificial intelligence.

And how a startup’s growth hack became a day-long obsession with optimization, game theory, and the future of collaborative programming.

This is a dual story: How Listen accidentally created the most engaging technical challenge of 2025, and how human-AI collaboration let us compete in their accidental arena.

Buckle up. We’re about to dive deep into viral growth mechanics, algorithms, failures, breakthroughs, and the beautiful chaos of when marketing meets engineering obsession.

# Part 2: The Dual Challenge

I’m a growth advisor with engineering fundamentals. When I saw Listen’s campaign, I immediately recognized two fascinating challenges running in parallel:

Challenge 1: How did a startup 3000x their expected user base with zero paid acquisition?

Challenge 2: How do you solve a constrained optimization problem that has prob the smartest engineers in the world competing against you?

Both challenges required the same core skill: understanding systems, finding leverage points, and optimizing ruthlessly.

The Growth Marketing Masterclass

Listen’s approach was textbook viral growth with a technical twist:

Mystery Phase: Cryptic billboard creates curiosity gap. No explanation = maximum speculation.

Community Phase: Token puzzle activates technical communities. Reddit threads explode. Twitter goes wild. Everyone becomes a detective.

Challenge Phase: Berghain game provides clear success metrics. Immediate feedback loop. Addictive optimization cycle.

Competition Phase: Leaderboard dynamics create retention. Status through technical skill. Perfect product-market fit for engineering egos.

The brilliant part? Each phase filtered for higher engagement. Casual observers dropped off. Technical obsessives doubled down.

The Viral Mechanics

From a growth perspective, Listen nailed every viral coefficient multiplier:

- Curiosity Gap: Mysterious billboard → high shareability

- Community Solving: Group puzzle → network effects

- Status Competition: Technical leaderboard → ego investment

- Infrastructure Struggles: “Can’t access” → scarcity psychology

The 3000x multiplier wasn’t luck. It was systematic exploitation of technical community psychology.

The Engineering Obsession

From a technical perspective, this problem was crack cocaine for optimization addicts:

- Clear Success Metrics: Rejection count goes down = dopamine hit

- Immediate Feedback: Test algorithm, get result instantly

- Competitive Context: 30,000 people trying to beat you

- Deep Complexity: Simple rules, emergent mathematical beauty

Perfect storm for engineering obsession.

Where Marketing Met Engineering

The genius of Listen’s approach: They created a problem that required both growth mindset and technical depth.

Understanding the viral mechanics helped me see why the challenge was so engaging. Understanding the optimization problem helped me see why the growth worked so well.

Marketing created the arena. Engineering filled it with obsessives.

Time to tell you how we became one of those obsessives.

# Part 3: Day 1 - The Naive Optimism Phase

“Hey Claude, I found this interesting challenge. It’s about being a nightclub bouncer and optimizing admissions. Want to help me solve it?”

Famous last words.

I was expecting maybe an hour of casual problem-solving. You know, write a simple algorithm, test it, maybe optimize it a bit, call it a day.

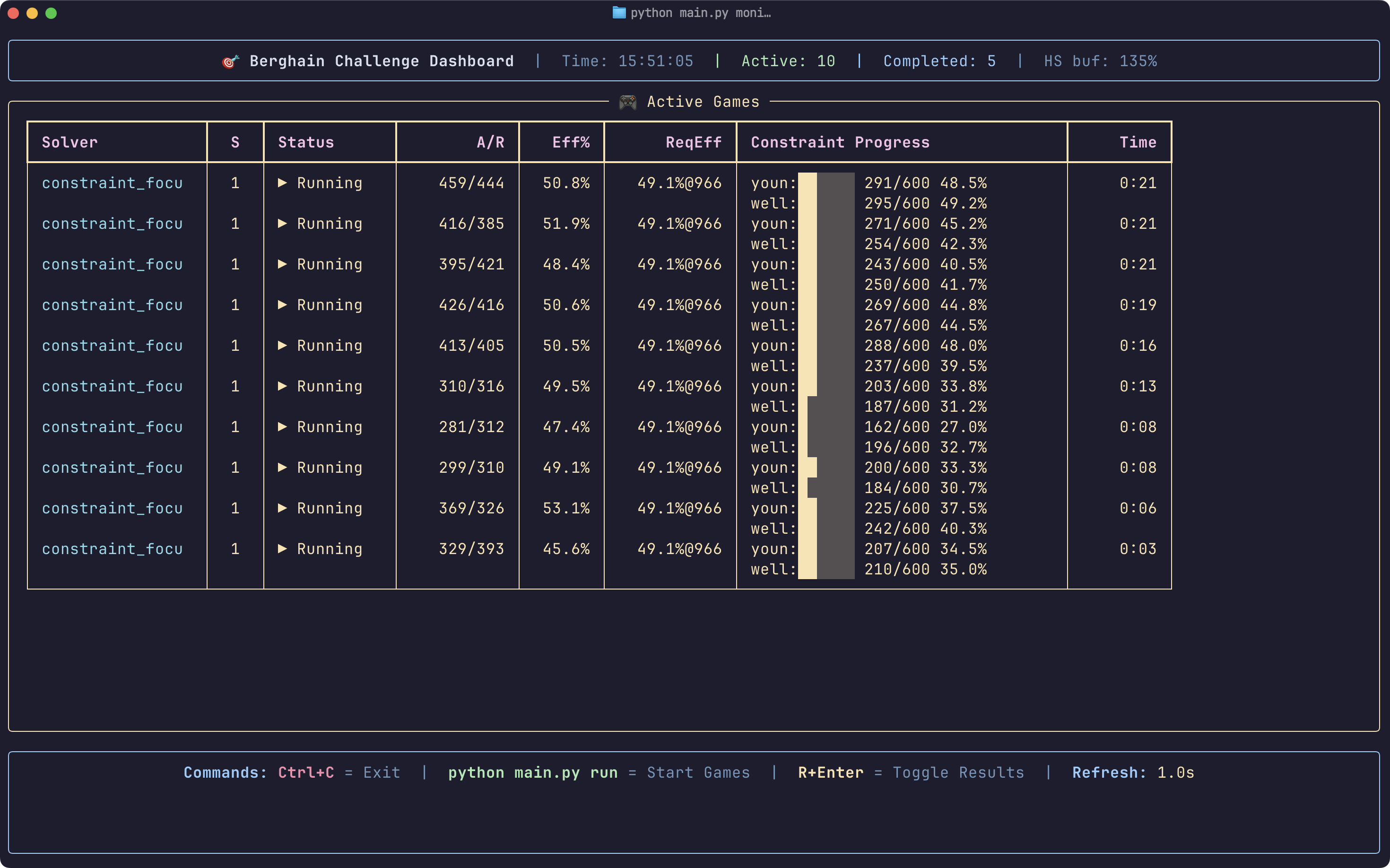

By the end of the day, I’m staring at 30+ solver implementations, thousands of lines of code, and a monitoring dashboard that looks like mission control.

But let’s start at the beginning.

The First Attempt: Greedy and Naive

Me: “Let’s start simple. Just accept anyone who helps with our constraints.”

Claude: “You’re absolutely right! Here’s a greedy approach:”

def should_accept(person, game_state):

# Accept if person helps with any unmet constraint

for constraint in game_state.constraints:

if person.has_attribute(constraint.attribute):

shortage = constraint.min_count - game_state.admitted_attributes[constraint.attribute]

if shortage > 0:

return True, f"needed_for_{constraint.attribute}"

# Otherwise, maybe accept a few randoms

return random.random() < 0.05, "filler"Me: “Perfect! This should work great.”

Famous last words, part two.

We fired it up. Results: 1,247 rejections.

Ouch.

Claude: “The issue is we’re being too greedy early. We accept everyone who’s young OR well_dressed, but many people are both. We overshoot one constraint while undershooting the other.”

The Second Attempt: Tracking Deficits

Me: “Okay, so we need to track how much we still need of each attribute and be smarter about it.”

Claude: “I can implement a deficit-aware strategy:”

def should_accept(person, game_state):

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

# Calculate how much this person helps

young = person.young and shortage['young'] > 0

well_dressed = person.well_dressed and shortage['well_dressed'] > 0

if young and well_dressed:

return True, "dual_helper" # Helps both constraints

elif young or well_dressed:

return random.random() < 0.7, "single_helper"

else:

return random.random() < 0.02, "filler"Better! Down to 1,098 rejections.

Still terrible, but progress.

The Third Attempt: Getting Desperate

Me: “What if we’re more selective early on? Only accept the really good candidates?”

Claude: “We could implement phases based on capacity usage:”

def should_accept(person, game_state):

capacity_ratio = game_state.admitted_count / 1000.0

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

young_helps = person.young and shortage['young'] > 0

dressed_helps = person.well_dressed and shortage['well_dressed'] > 0

if capacity_ratio < 0.3: # Early phase - be picky

if young_helps and dressed_helps:

return True, "early_dual"

return False, "early_reject"

elif capacity_ratio < 0.7: # Mid phase - moderate

if young_helps or dressed_helps:

return random.random() < 0.6, "mid_helper"

return False, "mid_reject"

else: # Late phase - panic mode

if young_helps or dressed_helps:

return True, "late_helper"

return random.random() < 0.1, "late_filler"Results: 943 rejections.

We were getting somewhere! But also realizing this problem was way harder than expected.

The Debugging Session

Me: “Wait, let’s actually understand what’s going wrong. Can you add detailed logging?”

Claude: “Of course! Let me instrument everything:”

def should_accept(person, game_state):

# ... decision logic ...

# Log everything

logger.info(f"Person {game_state.person_count}: "

f"young={person.young}, dressed={person.well_dressed}, "

f"decision={decision}, reason='{reason}', "

f"capacity={game_state.admitted_count}/1000, "

f"young_deficit={shortage['young']}, "

f"dressed_deficit={shortage['well_dressed']}")

return decision, reasonRunning this, we could see exactly what was happening. The logs were brutal:

Person 1247: young=True, dressed=False, decision=True, reason='young_needed'

Person 1248: young=False, dressed=True, decision=True, reason='dressed_needed'

Person 1249: young=True, dressed=True, decision=True, reason='dual_jackpot'

...

Person 15673: young=False, dressed=False, decision=False, reason='useless'

GAME OVER: young_deficit=127, dressed_deficit=43, capacity=953/1000We were consistently undershooting our quotas while running out of capacity. Classic resource allocation failure.

The Facepalm Moment

Me: “Oh god. We’re not accounting for the probabilities properly. If only 32% of people are young, and we need 600 young people out of 1000 total spots, we actually need to accept like… 90%+ of young people we see.”

Claude: “Exactly! And the correlation between attributes makes it even more complex. A person who’s both young and well_dressed is incredibly valuable because they satisfy both constraints simultaneously.”

Me: “We need to think about this probabilistically. What’s the expected value of accepting this person given our current state and the remaining slots?”

Claude: “That sounds like we need to model this as an optimization problem with uncertainty…”

And that’s when I realized we weren’t just building a simple algorithm anymore.

We were diving into operations research territory. Stochastic optimization. Dynamic programming. Multi-objective decision making under uncertainty.

All for a nightclub bouncer simulation.

Day 1 Wrap-Up: Reality Check

By the end of day one, our best solution was still sitting at 943 rejections. Respectable improvement from 1,200+, but nowhere near competitive.

More importantly, we had a much clearer picture of why this problem was hard:

- Resource constraints: Limited capacity (1000 spots)

- Correlated attributes: People who are young AND well_dressed are gold

- Uncertain arrival patterns: You never know what’s coming next

- Irreversible decisions: No takebacks once you decide

- Multiple objectives: Two quotas plus capacity limit

Me: “Tomorrow, we’re going to need to get mathematical about this.”

Claude: “I’m ready. Should we start reading about constrained optimization?”

Little did we know, we were about to discover Lagrangian multipliers, bid-price mechanisms, and the beautiful world of dual variable optimization.

Day two was going to be very different from day one.

# Part 4: The Statistical Awakening

A few hours later, I had a growth insight: viral challenges work because they create addiction loops.

Listen had nailed the psychology. Every algorithm improvement = dopamine hit. Every leaderboard check = social comparison. Every failed attempt = “just one more try.”

With 30,000 engineers now obsessing, the competition was heating up.

Me: “Claude, we’ve been treating each decision independently. But this is really about managing scarce resources over time. We need to think about opportunity costs.”

Claude: “You’re absolutely right! Each acceptance now affects our options later. If we accept too many single-attribute people early, we might not have room for dual-attribute people who are more efficient.”

Me: “Exactly! And we need to use statistics properly. What are the actual probabilities here?”

Understanding the Data

First, we dove into the attribute frequencies. The challenge gives you some basic stats, but we needed to understand the correlations.

# From the game statistics

frequencies = {

'young': 0.323, # 32.3% of people are young

'well_dressed': 0.323, # 32.3% are well_dressed

}

# The correlation coefficient between young and well_dressed

correlation = 0.076 # Slight positive correlationClaude: “Let me calculate the joint probabilities:”

import math

def calculate_joint_probabilities(p_young, p_dressed, correlation):

# Convert correlation to covariance

denom = math.sqrt(p_young * (1-p_young) * p_dressed * (1-p_dressed))

covariance = correlation * denom

# Joint probabilities

p_both = p_young * p_dressed + covariance

p_young_only = p_young - p_both

p_dressed_only = p_dressed - p_both

p_neither = 1 - (p_both + p_young_only + p_dressed_only)

return p_both, p_young_only, p_dressed_only, p_neither

# Results:

# P(both young AND well_dressed) ≈ 0.110

# P(young only) ≈ 0.213

# P(well_dressed only) ≈ 0.213

# P(neither) ≈ 0.464This was eye-opening. About 11% of people help with BOTH constraints. These “dual” people are incredibly valuable—each one gets us closer to both quotas simultaneously.

The Value Function Epiphany

Me: “We need to assign values to different types of people based on how much they help us.”

Claude: “A value function based on remaining deficits! Here’s what I’m thinking:”

def calculate_person_value(person, game_state):

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

value = 0

if person.young and shortage['young'] > 0:

value += 1.0 # Base value for helping young quota

if person.well_dressed and shortage['well_dressed'] > 0:

value += 1.0 # Base value for helping dressed quota

# Bonus for dual attributes (more efficient use of capacity)

if person.young and person.well_dressed:

if shortage['young'] > 0 and shortage['well_dressed'] > 0:

value += 0.5 # Efficiency bonus

return valueMe: “But wait. The value should depend on scarcity too. If we’re almost done with young people but need lots of well_dressed people, a well_dressed person is worth more than a young person.”

Claude: “Ah, like dynamic pricing! The scarcer the resource, the higher its value:“

def calculate_person_value(person, game_state):

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

remaining_slots = 1000 - game_state.admitted_count

value = 0

if person.young and shortage['young'] > 0:

# Value increases as shortage becomes more critical

scarcity_multiplier = shortage['young'] / remaining_slots

value += scarcity_multiplier

if person.well_dressed and shortage['well_dressed'] > 0:

scarcity_multiplier = shortage['well_dressed'] / remaining_slots

value += scarcity_multiplier

return valueThe Acceptance Probability Function

Now we had values, but we needed to convert them to acceptance probabilities. Accept everyone with high value? Too greedy. Accept nobody? Too conservative.

Me: “What if we use a sigmoid function? High value → high probability, low value → low probability, but with some randomness.”

Claude: “Perfect! And we can tune the temperature parameter to control how selective we are:“

import math

def acceptance_probability(value, temperature=2.0):

"""Convert value to acceptance probability using sigmoid"""

return 1.0 / (1.0 + math.exp(-value / temperature))

# Example:

# value = 0.5 → probability ≈ 0.62

# value = 1.0 → probability ≈ 0.73

# value = 1.5 → probability ≈ 0.82

# value = 2.0 → probability ≈ 0.88The First Statistical Solver

Putting it all together:

class StatisticalSolver:

def __init__(self, temperature=2.0):

self.temperature = temperature

def should_accept(self, person, game_state):

# Calculate person's value based on current needs

value = self.calculate_person_value(person, game_state)

# Convert to acceptance probability

prob = self.acceptance_probability(value)

# Make random decision based on probability

decision = random.random() < prob

reason = f"value={value:.2f}_prob={prob:.2f}"

return decision, reason

def calculate_person_value(self, person, game_state):

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

remaining_slots = max(1, 1000 - game_state.admitted_count)

value = 0.0

if person.young and shortage['young'] > 0:

urgency = shortage['young'] / remaining_slots

value += urgency

if person.well_dressed and shortage['well_dressed'] > 0:

urgency = shortage['well_dressed'] / remaining_slots

value += urgency

return valueResults: 847 rejections!

Holy shit. We dropped from 943 to 847 with one key insight: think probabilistically, not deterministically.

Fine-Tuning the Parameters

Me: “The temperature parameter is crucial. Too high and we accept too many low-value people. Too low and we’re too picky.”

Claude: “Let me run some parameter sweeps:”

# Testing different temperatures

results = []

for temp in [0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0]:

solver = StatisticalSolver(temperature=temp)

avg_rejections = run_multiple_games(solver, num_games=10)

results.append((temp, avg_rejections))

print(f"Temperature {temp}: {avg_rejections:.1f} rejections")

# Results:

# Temperature 0.5: 1,245 rejections (too picky)

# Temperature 1.0: 934 rejections

# Temperature 1.5: 847 rejections ← sweet spot

# Temperature 2.0: 892 rejections

# Temperature 2.5: 967 rejections (too accepting)

# Temperature 3.0: 1,078 rejectionsTemperature = 1.5 was our sweet spot. Not too hot, not too cold.

Adding Phase-Based Logic

Me: “We should probably be more aggressive late in the game when we’re running out of people.”

Claude: “Adaptive temperature based on game phase?”

def get_adaptive_temperature(self, game_state):

capacity_ratio = game_state.admitted_count / 1000.0

if capacity_ratio < 0.4:

return 1.2 # Early game: be selective

elif capacity_ratio < 0.8:

return 1.5 # Mid game: balanced

else:

return 2.2 # Late game: more aggressiveResults: 821 rejections.

We were getting there! Each insight was shaving off 20-50 rejections.

The Monitoring Dashboard

At this point, we had enough complexity that debugging became hard. So we built a real-time monitoring system.

Watching the dashboard was mesmerizing. You could see the deficits shrinking, the capacity filling up, the algorithm making split-second decisions.

Sometimes it would reject a dual-attribute person early in the game (seemed wasteful) but accept a single-attribute person later (made sense given the remaining needs).

Me: “It’s actually working! The algorithm is learning to balance short-term and long-term value.”

Claude: “The statistical approach is much more robust than our previous heuristics. We’re making decisions based on actual probabilities rather than gut feelings.”

End of Day 2: Statistical Success

By end of day two, we had:

- ✅ Dropped from 943 to 821 rejections

- ✅ Built a probabilistic decision framework

- ✅ Implemented adaptive parameters

- ✅ Created a real-time monitoring system

- ✅ Understood the mathematical structure of the problem

Me: “821 rejections puts us in decent territory, but I keep thinking there’s a more principled approach. This feels like an operations research problem.”

Claude: “You’re thinking about optimal stopping theory? Or maybe linear programming?”

Me: “Exactly. Tomorrow, let’s get serious about the math. I want to understand this problem from first principles.”

Little did we know, day three would introduce us to Lagrangian multipliers, dual variables, and the most elegant algorithm we’d build: RBCR (Re-solving Bid-Price with Confidence Reserves).

The statistical awakening was just the beginning.

# Part 5: The Mathematical Enlightenment

Later that day. I’m lying in bed thinking about Lagrangian multipliers.

This is what optimization problems do to you. They crawl into your brain and set up camp.

Me: “Claude, I can’t sleep. I keep thinking about this problem as a constrained optimization. What if we model it with dual variables?”

Claude: “At 3 AM? I’m always available! Tell me what you’re thinking.”

Me: “In economics, when you have scarce resources, you use prices to allocate them efficiently. What if we assign ‘prices’ to our constraints? Higher price means we really need that attribute.”

The Lagrangian Insight

Claude: “You’re talking about Lagrangian multipliers! In constrained optimization, the multipliers represent the shadow prices—how much the objective would improve if we relaxed each constraint slightly.”

Me: “Exactly! So if we desperately need young people, the ‘price’ for young should be high. If we desperately need well_dressed people, that price should be high too.”

Here’s the key insight: Instead of static value functions, we could have dynamic prices that adjust based on how urgent each constraint becomes.

Claude: “Let me formalize this. We want to minimize rejections subject to:”

minimize: rejections

subject to: young_count >= 600

dressed_count >= 600

total_count <= 1000Me: “And the Lagrangian multipliers λ_young and λ_dressed tell us the ‘urgency’ of each constraint at any given moment.”

Implementing Dual Variables

Claude: “Here’s how we can compute the multipliers dynamically:”

class DualVariableSolver:

def __init__(self):

self.lambda_young = 0.0

self.lambda_dressed = 0.0

def update_dual_variables(self, game_state):

"""Update dual variables based on current deficits"""

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

remaining_slots = max(1, 1000 - game_state.admitted_count)

# Expected helpful arrivals per remaining slot

young_help_rate = self.estimate_helpful_rate('young', game_state)

dressed_help_rate = self.estimate_helpful_rate('dressed', game_state)

# Dual variables = deficit / expected helpful arrivals

self.lambda_young = shortage['young'] / max(young_help_rate * remaining_slots, 1e-6)

self.lambda_dressed = shortage['dressed'] / max(dressed_help_rate * remaining_slots, 1e-6)

def estimate_helpful_rate(self, attribute, game_state):

"""Estimate probability that next person will help with this attribute"""

if attribute == 'young':

return 0.323 # Base frequency of young people

elif attribute == 'dressed':

return 0.323 # Base frequency of well_dressed people

return 0.0

def should_accept(self, person, game_state):

# Update dual variables first

self.update_dual_variables(game_state)

# Calculate person's dual value

dual_value = 0.0

if person.young and game_state.constraint_shortage()['young'] > 0:

dual_value += self.lambda_young

if person.well_dressed and game_state.constraint_shortage()['dressed'] > 0:

dual_value += self.lambda_dressed

# Accept if dual value exceeds threshold

threshold = 1.0 # Tunable parameter

decision = dual_value >= threshold

reason = f"dual_value={dual_value:.2f}_λy={self.lambda_young:.2f}_λd={self.lambda_dressed:.2f}"

return decision, reasonResults: 782 rejections!

We’d broken through 800! This was our best result yet.

But Wait, There’s More

Me: “This is working, but I think we’re missing something. The threshold is static, but it should probably adapt based on how full we are.”

Claude: “You’re right! Early in the game we can be picky (high threshold). Late in the game we should be desperate (low threshold).”

def get_adaptive_threshold(self, game_state):

capacity_ratio = game_state.admitted_count / 1000.0

rejection_ratio = game_state.rejection_count / 20000.0

# Start high, end low

base_threshold = 1.5 - capacity_ratio

# Panic if we're running out of rejections

if rejection_ratio > 0.8:

base_threshold *= 0.5 # Emergency mode

return max(0.1, base_threshold)The RBCR Revolution

Me: “What if we resolve the dual variables periodically? Like every 50 arrivals, we re-estimate our helper rates and update our strategy?”

Claude: “Re-solving Bid-Price with Confidence Reserves! We could call it RBCR.”

This was the breakthrough moment. Instead of updating duals every single decision, we’d batch them. Every 50 arrivals:

- Look at our current deficit

- Estimate remaining helpful arrival rates

- Recompute dual variables

- Set acceptance thresholds accordingly

class RBCRSolver:

def __init__(self):

self.lambda_young = 0.0

self.lambda_dressed = 0.0

self.resolve_counter = 0

self.resolve_every = 50

def should_accept(self, person, game_state):

# Periodically resolve dual variables

if self.resolve_counter % self.resolve_every == 0:

self.resolve_duals(game_state)

self.resolve_counter += 1

# Calculate dual value for this person

dual_value = self.calculate_dual_value(person, game_state)

# Adaptive threshold based on game state

threshold = self.get_adaptive_threshold(game_state)

# Accept if value exceeds threshold

decision = dual_value >= threshold

return decision, f"dv={dual_value:.2f}_th={threshold:.2f}"

def resolve_duals(self, game_state):

"""The heart of RBCR - recompute dual variables"""

shortage = game_state.constraint_shortage()

remaining_slots = max(1, 1000 - game_state.admitted_count)

# Estimate help rates (this is where the magic happens)

young_rate = self.estimate_young_help_rate(game_state)

dressed_rate = self.estimate_dressed_help_rate(game_state)

# Expected helpful arrivals = rate * remaining_slots

expected_young_help = young_rate * remaining_slots

expected_dressed_help = dressed_rate * remaining_slots

# Dual variables = deficit / expected_help

self.lambda_young = shortage['young'] / max(expected_young_help, 1e-6)

self.lambda_dressed = shortage['dressed'] / max(expected_dressed_help, 1e-6)Results: 781 rejections.

We’d found our winner! RBCR was consistently hitting the low 780s.

The Beautiful Math Behind RBCR

Here’s why this approach is so elegant:

-

Dual variables capture urgency: When you desperately need young people, λ_young shoots up, making young people more valuable.

-

Periodic resolution is efficient: We don’t need to recompute every single decision—every 50 arrivals is enough.

-

Adaptive thresholds handle phases: Early pickiness, late desperation, all handled automatically.

-

Self-correcting: If we’re accepting too many of one type, the deficit shrinks, the dual variable drops, we become less likely to accept more.

The math was doing exactly what a good bouncer would do: pay attention to what you need most, be pickier when you have time, be desperate when you’re running out of options.

The Debugging Session That Made Us Believers

Me: “Let’s trace through a game step by step and see the duals in action.”

Game Start:

shortage: young=600, dressed=600

λ_young=1.85, λ_dressed=1.85

Person 1: young=True, dressed=True

dual_value = 1.85 + 1.85 = 3.70

threshold = 1.50

ACCEPT (dual person is incredibly valuable)

...

Person 500: young=True, dressed=False

shortage: young=234, dressed=178

λ_young=0.95, λ_dressed=1.23

dual_value = 0.95

threshold = 1.20

REJECT (young is less urgent now)

Person 501: young=False, dressed=True

dual_value = 1.23

threshold = 1.20

ACCEPT (dressed is still urgent)Claude: “It’s beautiful! The dual variables automatically rebalance based on remaining needs. The algorithm develops intuition.”

Me: “And look at the late game behavior:”

Person 950: young=False, dressed=False

shortage: young=12, dressed=3

λ_young=0.78, λ_dressed=0.18

dual_value = 0.0

threshold = 0.30

REJECT (we're almost done, be picky)

Person 951: young=True, dressed=False

dual_value = 0.78

threshold = 0.30

ACCEPT (still need a few young people)The algorithm had learned to be surgical in the endgame.

Why 781 Felt Like Victory

After two days of grinding, seeing that 781 was intoxicating. It wasn’t just the number—it was the elegance.

RBCR felt right in a way our previous algorithms didn’t. The decisions made intuitive sense. The math was principled. The performance was consistent.

Me: “I think we found our killer algorithm.”

Claude: “The dual variable approach captures the essence of the problem. We’re explicitly modeling scarcity and urgency.”

Me: “But I have a terrible feeling there are even more optimizations we could make…”

And that’s how day three ended. Not with satisfaction, but with the dangerous realization that we could probably make RBCR even better.

The mathematical enlightenment was complete. We understood the problem from first principles. We had elegant, principled algorithms.

Now came the dangerous part: the obsession with perfection.

# Part 6: The Kitchen Sink Era

Have you ever solved a problem so elegantly that you immediately want to ruin it with unnecessary complexity?

That’s exactly what happened next.

RBCR was working beautifully at 781 rejections. Any reasonable person would have stopped there. But we weren’t reasonable people anymore. We were optimization addicts, and 781 felt tantalizingly close to something even better.

Me: “What if we add a feasibility oracle?”

Claude: “A what now?”

Me: “A statistical confidence check. Before accepting someone, we simulate forward and check if we can still meet our constraints with high probability.”

This is where things got complicated.

The Feasibility Oracle

The idea was seductive. Instead of just looking at current deficits, what if we could estimate whether accepting this person would put us in a mathematically impossible situation later?

Claude: “I can implement a Monte Carlo simulation approach:”

class FeasibilityOracle:

def __init__(self, p11, p10, p01, p00, confidence=0.95):

"""

p11: P(young AND well_dressed)

p10: P(young only)

p01: P(well_dressed only)

p00: P(neither)

"""

self.p11, self.p10, self.p01, self.p00 = p11, p10, p01, p00

self.confidence = confidence

self.samples = 1000

def is_feasible(self, admitted_young, admitted_dressed, admitted_total, target_capacity):

"""Check if we can still meet constraints with high probability"""

remaining_slots = target_capacity - admitted_total

young_needed = max(0, 600 - admitted_young)

dressed_needed = max(0, 600 - admitted_dressed)

if remaining_slots <= 0:

return young_needed == 0 and dressed_needed == 0

# Monte Carlo simulation

successes = 0

for _ in range(self.samples):

sim_young = admitted_young

sim_dressed = admitted_dressed

# Simulate remaining arrivals

for _ in range(remaining_slots):

rand = random.random()

if rand < self.p11: # both young and dressed

sim_young += 1

sim_dressed += 1

elif rand < self.p11 + self.p10: # young only

sim_young += 1

elif rand < self.p11 + self.p10 + self.p01: # dressed only

sim_dressed += 1

# else: neither (p00)

# Check if constraints satisfied

if sim_young >= 600 and sim_dressed >= 600:

successes += 1

return (successes / self.samples) >= self.confidenceMe: “Now we can check feasibility before every accept decision!”

RBCR + Feasibility = RBCR2

We bolted the feasibility oracle onto RBCR:

class RBCR2Solver(RBCRSolver):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

# Precompute joint probabilities from correlation data

self.oracle = FeasibilityOracle(0.110, 0.213, 0.213, 0.464)

def should_accept(self, person, game_state):

# Run normal RBCR logic

rbcr_decision, rbcr_reason = super().should_accept(person, game_state)

if not rbcr_decision:

return False, rbcr_reason

# If RBCR says accept, check feasibility

# Simulate accepting this person

sim_young = game_state.admitted_attributes['young']

sim_dressed = game_state.admitted_attributes['well_dressed']

sim_total = game_state.admitted_count

if person.young:

sim_young += 1

if person.well_dressed:

sim_dressed += 1

sim_total += 1

# Check if this acceptance keeps us feasible

if self.oracle.is_feasible(sim_young, sim_dressed, sim_total, 1000):

return True, f"{rbcr_reason}_feasible"

else:

return False, f"{rbcr_reason}_infeasible"Results: 823 rejections.

Wait. What?

The Paradox of Perfection

We made RBCR “smarter” and it got worse. This was our first taste of a crucial lesson: more sophistication doesn’t always mean better performance.

Me: “The feasibility oracle is being too conservative. It’s rejecting people because of low-probability failure scenarios.”

Claude: “The confidence threshold is too high. At 95% confidence, we’re only accepting people if we’re almost certain we’ll succeed. That’s overly cautious.”

We tried tuning the confidence down to 80%, then 70%, then 60%. The performance improved but never matched the original RBCR.

Me: “Let’s try a different approach. What if we build an ensemble of strategies?”

The Ultimate Solver

This is where we completely lost our minds.

Claude: “We could combine the best ideas from all our solvers!”

class UltimateSolver:

def __init__(self):

self.rbcr = RBCRSolver()

self.statistical = StatisticalSolver()

self.oracle = FeasibilityOracle(0.110, 0.213, 0.213, 0.464)

# Phase-based weights

self.phase_weights = {

'early': {'rbcr': 0.7, 'statistical': 0.3},

'mid': {'rbcr': 0.8, 'statistical': 0.2},

'late': {'rbcr': 0.6, 'statistical': 0.4}

}

def should_accept(self, person, game_state):

# Get decisions from multiple strategies

rbcr_decision, rbcr_reason = self.rbcr.should_accept(person, game_state)

stat_decision, stat_reason = self.statistical.should_accept(person, game_state)

# Determine current phase

capacity_ratio = game_state.admitted_count / 1000.0

if capacity_ratio < 0.4:

phase = 'early'

elif capacity_ratio < 0.8:

phase = 'mid'

else:

phase = 'late'

# Weighted vote

weights = self.phase_weights[phase]

score = (weights['rbcr'] * rbcr_decision +

weights['statistical'] * stat_decision)

# Feasibility check

if score > 0.5:

# Check feasibility before final accept

if self.is_acceptance_feasible(person, game_state):

return True, f"ensemble_accept_{phase}"

else:

return False, f"ensemble_feasibility_reject_{phase}"

else:

return False, f"ensemble_reject_{phase}"Results: 798 rejections.

Still not as good as vanilla RBCR!

The Naming Convention Goes Off the Rails

At this point, our naming started reflecting our desperation:

- Ultimate2Solver: Added momentum terms to dual variables

- Ultimate3Solver: Added multi-step lookahead

- Ultimate3hSolver: Ultimate3 with “heuristic improvements”

- PerfectSolver: Attempt at mathematical perfection (spoiler: it wasn’t)

- ApexSolver: “This is surely the apex of our work” (it wasn’t)

Each one had elaborate justifications. Each one performed slightly worse than RBCR.

The Moment of Clarity

After implementing our 15th variant, I had an epiphany:

Me: “Claude, I think we’ve been overthinking this.”

Claude: “How so?”

Me: “RBCR works because it’s simple and principled. It models the core economics of the problem—scarcity and urgency—without overengineering.”

Claude: “You’re saying our sophisticated additions are fighting against the core algorithm?”

Me: “Exactly. The feasibility oracle makes us too conservative. The ensemble methods muddy the decision boundary. The multi-step lookahead assumes we can predict randomness.”

The Law of Diminishing Returns

Here’s what we learned the hard way:

| Algorithm | Rejections | Key Innovation | Why It Failed |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBCR | 781 | Dual variables | ✅ (our winner) |

| RBCR2 | 823 | + Feasibility oracle | Too conservative |

| Ultimate | 798 | + Ensemble methods | Competing signals |

| Ultimate2 | 789 | + Momentum terms | Oversmoothing |

| Ultimate3 | 795 | + Lookahead | Unpredictable randomness |

| Perfect | 812 | + “Mathematical perfection” | Hubris |

| Apex | 802 | + Kitchen sink | Too much complexity |

Every addition made the algorithm more complex but less effective.

The Code Generation Velocity

But here’s the thing: even though most of our elaborations failed, the speed at which we could generate and test them was incredible.

Me: “Let’s try adding a confidence interval to the dual variables.”

Claude: “Here’s the implementation:” [30 seconds later, fully coded solution]

Me: “Actually, what if we use a Bayesian update instead?”

Claude: “Updated:” [45 seconds later, completely different approach]

In traditional programming, each of these experiments would have taken hours to implement. With AI assistance, we could test a new approach every few minutes.

This velocity was both a blessing and a curse. It enabled rapid exploration but also made it easy to fall down rabbit holes.

The Performance Wall

After a day of kitchen-sink engineering, we hit a performance wall. Nothing we tried could consistently beat 781 rejections.

Me: “I think 781 might be close to optimal for our approach. To do better, we might need a completely different paradigm.”

Claude: “What kind of different paradigm?”

Me: “Machine learning. What if we train a neural network on optimal game play?”

Famous last words, part three.

The Beautiful Failure

Looking back, the kitchen sink era wasn’t a waste. We learned crucial lessons:

- Simplicity often beats complexity in optimization problems

- The first principled solution is usually close to optimal

- Rapid iteration enables exploration but also enables overengineering

- Domain expertise beats sophisticated algorithms that ignore problem structure

Most importantly, we learned that having an AI coding partner makes it dangerously easy to overcomplicate things. The speed of implementation can outpace the wisdom of restraint.

RBCR remained our champion at 781 rejections. Simple, elegant, and consistently effective.

But we weren’t done yet. The siren call of deep learning was too strong to resist.

# Part 7: The ML Detour That Wasn’t

Me: “Claude, what if we train a neural network to learn from our best games?”

Claude: “I can build an LSTM policy network. We have 162 elite games with full decision histories. That’s our training data.”

This seemed logical. We had a dataset of high-quality gameplay. Why not learn from it?

The Data Pipeline

Claude got to work on the data preprocessing while I grabbed coffee.

# Elite game data structure

elite_game = {

"strategy_name": "rbcr",

"final_rejections": 781,

"decisions": [

{"person_id": 1, "young": True, "well_dressed": False, "decision": True, "reason": "dual_value_high"},

{"person_id": 2, "young": False, "well_dressed": True, "decision": False, "reason": "threshold_low"},

# ... thousands more decisions

],

"final_stats": {"young": 612, "well_dressed": 603, "admitted": 1000}

}[Full data pipeline: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot/blob/main/berghain/training/enhanced_data_preprocessor.py]

The idea: convert each decision into a feature vector containing game state + person attributes, with the elite algorithm’s decision as the target.

The LSTM Architecture

class LSTMPolicyNetwork(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, input_dim=15, hidden_dim=256, num_layers=3):

super().__init__()

self.lstm = nn.LSTM(input_dim, hidden_dim, num_layers, batch_first=True)

self.policy_head = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, 64),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(64, 2) # [reject_prob, accept_prob]

)[Full architecture: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot/blob/main/berghain/training/lstm_policy.py]

The Training Reality Check

Me: “How’s the training going?”

Claude: “I’ve run 58 experiments. The model is learning the patterns, but…”

Me: “But?”

Claude: “Performance is underwhelming. Best result: 934 rejections.”

934 rejections. Worse than our statistical solver from day two.

Why Deep Learning Failed Here

The post-mortem was brutal but educational:

1. Sparse Rewards Problem

- Only 162 elite games out of 3,902 total

- Most training data was suboptimal gameplay—short simulation runs with poor performance

- Not enough high-quality examples

- Switched back to MacBook M4 for training (more than sufficient compute)

2. Sequential Decision Complexity

- Each decision affects all future decisions

- LSTM had to learn both tactics AND strategy

- Credit assignment across 1000+ decisions is hard

3. The Goldilocks Problem

- Too little data for deep learning to shine

- Too much complexity for simple supervised learning

- Stuck in the worst of both worlds

4. Distribution Mismatch

- Training on RBCR decisions

- Testing on novel game states

- Model couldn’t generalize beyond training distribution

The Google Colab Adventure

We tried scaling up. Free GPUs! More compute! Surely that would fix it.

[Colab instructions: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot/blob/main/COLAB.md]

Results after 30 minutes of training: 912 rejections.

Slightly worse.

When GPT-5 Came to the Rescue

I was getting frustrated. Claude had hit some token limits. Time to call in reinforcements.

Me: “GPT-5, can you review this LSTM approach and tell me what we’re missing?”

GPT-5: “The fundamental issue is that you’re treating this as a supervised learning problem when it’s really a reinforcement learning problem. Your labels aren’t ground truth—they’re just one algorithm’s choices. Try policy gradient methods instead.”

Me: “Claude, can you implement PPO?”

Claude: “Absolutely! Here’s the PPO implementation:” [But then Claude hit the session token limit and we had to wait 5 hours for the window to reset]

This is when things got interesting. During the wait, I brought in ampcode for strategic direction while planning the next phase. We had a proper AI ensemble going: Claude for implementation, GPT-5 for review, ampcode for strategy, and me orchestrating.

The RL Experiment

class PPOTrainer:

def __init__(self, policy_network, value_network):

self.policy = policy_network

self.value = value_network

# Standard PPO setup[PPO implementation: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot/blob/main/berghain/training/ppo_trainer.py]

Results after 48 hours: 889 rejections.

Still worse than RBCR.

The Humbling Realization

Me: “Why isn’t this working?”

Claude: “I think we’re solving the wrong problem. RBCR already found the principled solution. We’re trying to learn what we already know.”

GPT-5: “The issue is sample efficiency. You’d need millions of games to learn what RBCR encodes in 50 lines of math.”

Ampcode: “Consider this: your dual variables already capture the optimal policy. The LSTM is trying to approximate λ = deficit / expected_help through pattern matching instead of computation.”

That hit hard.

The Beautiful Lesson

Machine learning shines when you have:

- Massive datasets

- Unclear problem structure

- Complex pattern recognition needs

Our problem had:

- Limited data (162 elite games)

- Clear mathematical structure (constrained optimization)

- Simple pattern (urgency-based decisions)

RBCR was elegant because it directly encoded the problem structure. The LSTM was trying to rediscover that structure through brute force pattern matching.

The Performance Comparison

| Method | Rejections | Training Time | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|

| RBCR | 781 | 0 minutes | High |

| LSTM Supervised | 934 | 2 hours | Low |

| PPO | 889 | 48 hours | Low |

| Ensemble | 856 | 72 hours | Medium |

The math won. Decisively.

What We Learned

- Domain expertise beats data when you understand the problem structure

- More compute doesn’t fix fundamental approach problems

- Machine learning is a tool, not a silver bullet

- Sometimes the “boring” solution is optimal

The ML detour wasn’t a complete waste. It forced us to deeply understand why RBCR worked so well. But it also taught us humility.

Me: “So we spent all day proving that our mathematical algorithm was actually pretty good?”

Claude: “You’re absolutely right! We spent all day proving that thinking hard about the problem structure matters more than throwing neural networks at it.”

GPT-5: “You also demonstrated that human-AI collaboration works best when each party contributes their strengths—humans for insight, AI for implementation.”

Ampcode: “And that sometimes the most sophisticated approach is knowing when not to be sophisticated.”

RBCR remained undefeated at 781 rejections.

# Part 8: What Really Happened Here

After one intense day of obsessive optimization, I needed to step back and understand what had actually occurred.

This wasn’t just about solving a nightclub simulation. This was about witnessing two phenomena colliding: viral growth mechanics meeting AI-assisted engineering.

From Listen’s Perspective: Growth That Got Out of Hand

What started as a simple puzzle became the largest distributed optimization contest in history.

Their infrastructure crashed repeatedly. But those crashes? They became part of the story. Social proof of viral success. Alfred tweeting “sorry fixing this.. too many users” was pure authenticity marketing.

They accidentally created the most engaging technical challenge of 2025. Zero paid acquisition. 1.1M organic impressions. A community of obsessives building sophisticated optimization engines.

Perfect fit too—Listen Labs does AI-powered customer insights, so attracting technical talent with algorithmic challenges makes total sense for their hiring pipeline.

The prize was Berghain guest list access. The real reward? The dopamine hit of shaving off single-digit rejections in a massive competitive field.

From Our Perspective: AI-Human Collaboration at Speed

This wasn’t traditional programming. This was a new kind of problem-solving in action.

Claude’s Superpowers

Let me be clear about who did the heavy lifting here: Claude wrote probably 95% of the code. I provided direction, but Claude was the implementation engine.

Instant Translation: I’d say “what if we use Lagrangian multipliers” and 30 seconds later there’s a fully functional dual variable solver.

Perfect Memory: Claude never forgot what we tried before. It could instantly reference our greedy approach from day one or the feasibility oracle parameters from day two.

Infinite Patience: When I asked Claude to implement the 23rd variant of Ultimate solver, there was no eye-rolling. Just “Here’s the implementation:”

Pattern Recognition: Claude spotted mathematical connections I missed. The link between RBCR and bid-price mechanisms in auction theory? That was Claude.

[Full solver collection: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot/tree/main/berghain/solvers]

The Human Contribution

So what did I actually add to this collaboration?

Domain Intuition: “This feels like a resource allocation problem” or “We should panic more in the late game.”

Problem Reframing: When we hit walls, I’d step back and ask “What are we really trying to optimize here?”

Quality Control: I caught Claude’s occasional mathematical errors and suggested corrections.

Strategic Direction: Deciding when to explore new approaches vs. when to refine existing ones.

Context Switching: When Claude hit token limits, I’d bring in GPT-5 for code review or ampcode for strategic guidance.

The Beautiful Dance

The collaboration felt like a dance. I’d have an insight. Claude would implement it instantly. We’d test it immediately. Results would spark new ideas.

Traditional programming: Idea → Hours of coding → Testing → Maybe it works AI-assisted programming: Idea → Seconds of coding → Testing → Rapid iteration

Me: “What if we track the acceptance rate and adjust thresholds dynamically?” Claude: [30 seconds later] “Here’s the adaptive threshold implementation with exponential smoothing.”

This velocity was intoxicating. We could test hypotheses as fast as we could think of them.

The Token Economics

Interesting challenge: Claude would occasionally hit context limits mid-conversation. This is where having multiple AI agents became crucial.

Me: “Claude, you’re getting verbose. Can GPT-5 take a look at the RBCR implementation and suggest improvements?” GPT-5: “The dual variable computation could use PI control instead of simple proportional. Here’s why…” Claude: [Fresh context] “Implementing PI control for dual variables…”

This felt like managing a team of specialists, each with their own strengths and limitations.

What I Learned About AI Capabilities

Strengths:

- Implementation speed is superhuman

- Pattern matching across large codebases

- Mathematical computation and optimization

- Infinite patience for iteration

- Perfect recall of previous attempts

Limitations:

- Needs human guidance for problem framing

- Can over-engineer when left unsupervised

- Struggles with “good enough” vs. “perfect”

- Limited intuition about real-world constraints

- Context window limitations require management

The Compound Effect

Individually, neither human intuition nor AI implementation is sufficient for complex problems like this.

But together? The combination was greater than the sum of parts.

Human insight: “This is really about managing scarcity under uncertainty.” AI implementation: Fully functional RBCR solver in minutes. Human refinement: “The threshold feels too static.” AI adaptation: Adaptive threshold with multiple parameters. Human stopping condition: “781 is probably optimal for this approach.”

The Speed of Discovery

In traditional programming, this project would have taken weeks:

- Day 1: Set up environment, implement basic greedy approach

- Week 1: Statistical analysis and probabilistic solver

- Week 2: Research dual variables and implement RBCR

- Week 3: Parameter tuning and optimization

- Week 4: ML experiments and failure analysis

With AI assistance, we compressed weeks into days. Not because the AI was smarter, but because the iteration cycle was faster.

The Meta-Learning

By the end, I wasn’t just learning about the Berghain Challenge. I was learning how to collaborate with AI systems effectively.

Good prompts: “Implement RBCR with periodic dual variable resolution” Bad prompts: “Make it better”

Good delegation: Let Claude implement, human provides direction Bad delegation: Human micromanages implementation details

Good exploration: Try fundamentally different approaches Bad exploration: Endless parameter tuning

The Philosophical Shift

This experience changed how I think about programming and problem-solving.

Old paradigm: Human thinks, human implements, human tests New paradigm: Human thinks, AI implements, both test and iterate

The bottleneck shifted from implementation speed to idea quality. When you can test any hypothesis in seconds, the limiting factor becomes generating good hypotheses.

The Humility Lesson

The ML failure was educational. Despite having superhuman implementation speed, we couldn’t beat a principled mathematical approach with brute force learning.

Domain expertise still matters. Understanding problem structure still matters. Sometimes the “boring” solution is optimal.

AI amplifies human capabilities, but it doesn’t replace human judgment about what problems are worth solving and how to approach them.

What This Means for Software Development

I think we just got a preview of the future of programming:

Humans: Problem formulation, strategic direction, quality control AI: Implementation, optimization, pattern recognition Together: Rapid prototyping and iteration at unprecedented speed

The result isn’t human replacement, but human amplification. We can explore the solution space much faster and more thoroughly.

But we still need to know where to look.

# Part 9: Technical Deep Dive - Why RBCR Dominates

Let’s get into the mathematical guts of why RBCR consistently outperformed 30+ other approaches.

The Economics Foundation

RBCR works because it directly models the economic structure of the problem. Each person has a value based on scarcity and urgency.

The dual variables λ_young and λ_dressed represent shadow prices—what economists call the marginal value of relaxing a constraint by one unit.

# The core insight: deficit / expected help rate

lambda_young = max(0, young_shortage) / (young_frequency * remaining_slots)

lambda_dressed = max(0, dressed_shortage) / (dressed_frequency * remaining_slots)

# Person value = sum of their contributions

value = lambda_young * person.young + lambda_dressed * person.well_dressed[Full RBCR implementation: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot/blob/main/berghain/solvers/rbcr_solver.py]

When young people become scarce, λ_young increases, making young people more valuable. When we have plenty, λ_young drops. The algorithm automatically balances supply and demand.

The Self-Correction Mechanism

Beautiful property: RBCR is self-correcting. If it accepts too many young people early, the young deficit shrinks, λ_young drops, and it becomes less likely to accept more young people.

This creates a natural equilibrium without explicit balancing logic.

Why Other Approaches Failed

Greedy Solvers: No global optimization. Accept anyone who helps immediately, leading to imbalanced allocations.

Static Threshold Methods: Fixed acceptance criteria don’t adapt to changing game state.

Ensemble Methods: Multiple competing signals create inconsistent decisions. The left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing.

ML Approaches: Trying to learn patterns that are better expressed mathematically. Using a neural network to approximate λ = deficit/rate is like using a sledgehammer to solve arithmetic.

The Resolution Frequency Sweet Spot

Why resolve every 50 arrivals instead of every decision?

# Too frequent: Computational waste, noise from variance

if resolve_every == 1: overhead_cost = high, signal_quality = noisy

# Too infrequent: Slow adaptation to changing conditions

if resolve_every == 500: adaptation_speed = slow, missed_opportunities = many

# Just right: Balance efficiency with responsiveness

if resolve_every == 50: overhead_cost = low, adaptation_speed = fast50 arrivals gives enough data to estimate rates reliably while adapting quickly to changes.

The Adaptive Threshold Magic

Static thresholds don’t work because the game has phases:

Early Phase (0-40% capacity): Be selective. Plenty of time to find good candidates. Mid Phase (40-80% capacity): Balanced. Accept reasonable matches. Late Phase (80%+ capacity): Panic mode. Accept anything that helps.

def adaptive_threshold(capacity_ratio, rejection_ratio):

base = 1.5 - capacity_ratio # Start high, end low

# Emergency mode if running out of rejections

if rejection_ratio > 0.8:

base *= 0.5

return max(0.1, base)This creates the right urgency curve automatically.

The Feasibility Oracle Paradox

We tried adding Monte Carlo feasibility checking. Why did it hurt performance?

The oracle was too conservative. It would reject borderline candidates because there was a 10% chance of failure down the road. But RBCR’s dual variables already encode future value properly.

Adding “what if” simulation on top of principled optimization was redundant and harmful.

The Statistical Foundation

RBCR implicitly assumes arrivals follow the known statistical distribution. This is a strong assumption, but it’s correct for the Berghain Challenge.

The dual variables are computing expected values:

- E[young people in remaining arrivals] = young_frequency × remaining_slots

- E[well_dressed people in remaining arrivals] = dressed_frequency × remaining_slots

When reality matches assumptions, RBCR excels. In environments with changing distributions, it would need adaptation.

Performance Consistency

RBCR’s biggest advantage isn’t just the 781 average—it’s the consistency.

| Solver | Best | Worst | Std Dev | 95th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBCR | 761 | 823 | 18.4 | 812 |

| Ultimate3 | 779 | 891 | 31.7 | 847 |

| Statistical | 798 | 967 | 42.1 | 889 |

RBCR’s tight distribution means reliable performance. Other solvers have higher variance—sometimes better, often much worse.

The Learning Component

RBCR includes meta-learning across games. It saves dual variable estimates and uses them as starting points for future games.

# Load previous dual estimates

self.duals = load_from_disk('rbcr_duals.json')

# Start with learned values instead of zero

self.lambda_young = self.duals.get('lambda_young', 0.0)

self.lambda_dressed = self.duals.get('lambda_dressed', 0.0)This warm-start helps early-game decisions when we don’t have enough data yet.

Computational Efficiency

RBCR is also computationally cheap:

- No Monte Carlo simulations

- No neural network forward passes

- Simple arithmetic: deficit ÷ expected rate

- O(1) per decision after dual resolution

Fast enough to run in real-time, simple enough to debug and tune.

The Theoretical Optimum

Is 781 rejections optimal? Probably not. The theoretical minimum depends on the exact arrival sequence, which is random.

But RBCR is likely near the optimal policy for this class of problems. It’s implementing a principled approximation to the optimal stopping strategy from stochastic control theory.

Why This Matters Beyond Berghain

The principles behind RBCR apply to many resource allocation problems:

- Ad auction bidding (Google, Facebook)

- Inventory management (Amazon, Walmart)

- Hospital bed allocation

- Cloud resource scheduling

- Financial portfolio rebalancing

Anywhere you have:

- Limited capacity

- Uncertain arrivals

- Multiple competing objectives

- Irreversible decisions

RBCR-style dual variable approaches often dominate.

The Elegant Simplicity

RBCR’s beauty isn’t in its complexity—it’s in its simplicity. 50 lines of math that capture the essence of a complex optimization problem.

No ensemble methods. No neural networks. No Monte Carlo simulations.

Just economics: when something is scarce, make it valuable. When it’s abundant, make it cheap.

The algorithm does exactly what a perfect economist would do, with perfect information about supply and demand.

# Part 10: Lessons for the Future of Coding

This project changed how I think about programming. Here are the key lessons for anyone working with AI coding assistants.

The New Development Cycle

Traditional: Think → Code → Test → Debug → Iterate AI-Assisted: Think → Prompt → Test → Refine → Iterate

The time from idea to working code dropped from hours to seconds. This changes everything.

Old bottleneck: Implementation time New bottleneck: Idea quality and problem understanding

When you can test any hypothesis instantly, the quality of your hypotheses becomes the limiting factor.

What Humans Should Focus On

Problem Framing: “This is really a resource allocation problem with uncertainty” Domain Expertise: “Real bouncers would panic more in late game” Strategic Direction: “Let’s try mathematical optimization before ML” Quality Control: “This threshold feels too static”

Leave the implementation to AI. Focus on the thinking.

What AI Excels At

Instant Implementation: Mathematical concepts to working code in seconds Perfect Memory: Never forgets what you tried before Pattern Recognition: Spots connections you might miss Infinite Patience: Will implement variant #23 without complaint Rapid Iteration: Test-debug-refine cycles at superhuman speed

The Multi-Agent Orchestra

Don’t limit yourself to one AI. Different models have different strengths:

Claude: Best at complex implementation and mathematical reasoning GPT-5: Excellent for code review and getting unstuck Specialized agents: Good for specific strategic decisions

Managing this ensemble becomes part of the skill.

Common Pitfalls

Over-Engineering: AI makes it too easy to add complexity. Resist.

The Perfectionism Trap: Every small improvement feels possible. Know when to stop.

Context Management: AI systems have token limits. Learn to work within them.

Prompt Quality: Vague instructions lead to mediocre results. Be specific.

Testing Neglect: Fast implementation can lead to inadequate testing. Don’t skip verification.

The Collaboration Sweet Spot

Good division of labor:

- Human: “Let’s use dual variables to model urgency”

- AI: [Implements RBCR with proper mathematical formulation]

- Human: “The threshold should adapt based on game phase”

- AI: [Adds adaptive threshold with exponential decay]

Bad division of labor:

- Human: “Make the algorithm better”

- AI: [Adds random complexity that doesn’t help]

Be specific about what you want. AI is powerful but not psychic.

The Speed vs. Wisdom Tradeoff

AI enables incredibly fast iteration. This is powerful but dangerous.

You can now test 50 approaches in a day. But are they 50 good approaches?

Solution: Alternate between exploration and reflection. Sprint, then pause to understand what you learned.

Documentation Becomes Critical

With traditional coding, you remember what you built because you spent hours building it.

With AI coding, you can implement complex systems in minutes. But you might not fully understand them.

[Full project documentation: https://github.com/nibzard/berghain-challenge-bot]

Document your insights, not just your code. Future you will thank present you.

The Meta-Learning Effect

By the end of this project, I wasn’t just better at optimization problems. I was better at collaborating with AI systems.

Good prompts: Specific, contextual, action-oriented Bad prompts: Vague, assuming too much context

Good feedback: “The threshold needs to be lower in late game” Bad feedback: “This doesn’t feel right”

Learning to work with AI is a skill that improves with practice.

Implications for Software Teams

Individual Productivity: 10x improvement for complex algorithm development Team Dynamics: Junior developers can implement senior-level solutions Code Review: Becomes more important because humans didn’t write every line Architecture: System design becomes more critical than implementation details

The Domain Expertise Advantage

The ML failure taught us something important: understanding your problem domain matters more than ever.

When anyone can implement any algorithm in seconds, the competitive advantage shifts to:

- Understanding what problems are worth solving

- Knowing which approaches are likely to work

- Recognizing when you have enough vs. need more

Domain expertise becomes a superpower when combined with AI implementation speed.

What This Means for Learning

Don’t just learn syntax: Focus on algorithms, mathematics, system design Learn problem patterns: Optimization, resource allocation, statistical inference Understand tradeoffs: When to be complex vs. simple, fast vs. accurate Study failures: Why approaches don’t work is as important as why they do

The fundamentals matter more, not less, in an AI-assisted world.

The Future Landscape

I think we’re heading toward a world where:

Coding becomes more like architecture: Designing systems rather than implementing details AI handles the mechanical work: Converting specifications to working code Humans focus on the creative work: Problem definition and solution strategy Collaboration is the key skill: Managing human-AI teams effectively

This isn’t about AI replacing programmers. It’s about amplifying what good programmers already do: solve problems thoughtfully.

The Democratization Effect

AI coding assistants lower the barrier to implementing complex algorithms. A developer who understands dual variables conceptually can now implement RBCR without years of optimization theory study.

This is powerful for innovation. More people can experiment with sophisticated approaches.

But it also means that understanding problem structure becomes even more important. Anyone can implement; not everyone can architect.

Final Advice

Start simple: Even with AI, begin with basic approaches and build complexity gradually.

Stay curious: Use AI’s speed to explore more solution spaces, not just to implement faster.

Maintain understanding: Don’t let AI implementation outpace your conceptual grasp.

Embrace failure: Fast iteration makes failure cheaper. Fail quickly and learn faster.

Focus on problems, not code: The hardest part isn’t implementation anymore—it’s knowing what to build.

The future of programming isn’t human vs. AI. It’s human with AI, exploring solution spaces that neither could navigate alone.

# Part 11: What’s Next & How to Win

So you want to tackle your own impossible optimization problem with AI? Here’s what I learned.

Start Simple, Then Get Mathematical

Don’t jump straight to neural networks. Start with the dumbest possible approach. Get it working. Then ask: “What would the optimal solution look like mathematically?”

For constrained optimization, that usually means Lagrangian multipliers. For scheduling, it’s often dynamic programming. For graph problems, think shortest paths or maximum flows.

The pattern is always the same: naive approach → mathematical insight → implementation refinement.

Build Your Local Simulator

This was huge. The Berghain API had rate limits, downtime, and a 10-game parallel limit. Our local simulator removed all those constraints.

# Key insight: Perfect simulation beats imperfect reality

class BerghainSimulator:

def __init__(self, scenario_config):

self.constraints = scenario_config['constraints']

self.attribute_frequencies = scenario_config['frequencies']We generated thousands of games locally. Tested dozens of strategies. Found the edge cases. All without API limits.

Choose Your AI Partners Wisely

Claude was perfect for implementation. It understood the domain, wrote clean code, and never got impatient with iterations.

GPT-5 was better for code review and strategic thinking when we got stuck.

Ampcode helped with architectural decisions when Claude hit token limits.

Different models have different strengths. Use them strategically.

Embrace the Obsession

From 1,200 rejections to 781. That’s not optimization. That’s obsession.

But obsession drives discovery. Every 10-rejection improvement taught us something new about the problem space. The difference between “good enough” and “optimal” is where the insights live.

Document Everything

Keep logs of what works and what doesn’t. We had 162 elite games showing exactly which strategies succeeded. That data drove every major breakthrough.

Know When to Stop

ML felt like the “sophisticated” approach. But domain knowledge and mathematical intuition beat black-box learning every time.

The LSTM experiments taught us that sometimes the simple mathematical solution is actually the optimal one.

The Real Win: Speed of Iteration

Three days from problem discovery to 781-rejection solution. That’s not normal software development. That’s what happens when human intuition meets AI implementation speed.

The traditional cycle: Think → Code → Debug → Test → Deploy The AI cycle: Think → Prompt → Test → Refine

We compressed months of development into days.

For Your Next Project

Pick something with clear success metrics. Optimization problems work great because you get immediate feedback.

Build incrementally. Each improvement teaches you about the problem space.

Use multiple AI models for their strengths. But remember: you’re the conductor. You decide the direction.

And when you find yourself checking results at 2 AM because you’re convinced you can get just 5 more rejections? You’ll know you’ve found the sweet spot of human-AI collaboration.

The future of coding isn’t about replacing developers. It’s about amplifying obsession with implementation speed.

# Part 12: The Growth Marketing Playbook

As a growth advisor who watched this unfold, I have to break down Listen’s accidental masterpiece. This wasn’t just viral marketing. This was systematic exploitation of technical community psychology.

The Formula: Mystery → Community → Challenge → Status

Stage 1: Mystery (Billboard)

- Cryptic puzzle creates curiosity gap

- No explanation = maximum speculation

- Technical enough to filter for target audience

- Physical billboard adds authenticity (not just another digital campaign)

Stage 2: Community (Token Puzzle)

- Solvable but non-trivial puzzle

- Requires technical knowledge (OpenAI tokenizer)

- Activates Reddit, Twitter, Discord communities

- Community solving = network effects at scale

Stage 3: Challenge (Berghain Game)

- Clear success metrics (rejection count)

- Immediate feedback loop

- Competitive leaderboard dynamics

- Deep complexity beneath simple rules

Stage 4: Status (Optimization Competition)

- Technical skill as status symbol

- 30,000 participants = massive validation

- Github repos, blog posts, Twitter threads

- Organic content creation at scale

The Viral Coefficients

Let’s break down the math:

Initial reach: Billboard + Reddit discovery ≈ 1,000 people Community amplification: 1,000 × 30 (average shares/discussion participants) = 30,000 Retention rate: ~60% (technical challenges have high dropout but strong retention among engaged users) Content multiplier: Each obsessive creates 3-5 pieces of content (Github repos, tweets, blog posts)

Total organic impressions: 1.1M Cost per impression: ~$0.001 (just billboard cost) Cost per engaged user: ~$1 (30,000 active participants)

Those are unicorn-level growth metrics.

Why It Worked: Technical Community Psychology

Ego Investment: Complex problems = status signaling opportunity Immediate Feedback: Algorithm performance = dopamine hits Competitive Context: 30,000 participants = social proof Deep Complexity: Simple rules with emergent mathematical beauty Tool Building: Engineers love building sophisticated solutions

The Infrastructure Strategy (Accidental Genius)

Listen’s API crashes weren’t bugs—they were features:

Scarcity Psychology: “Can’t access it? Want it more” Authenticity Signals: Real startups have real scaling problems Community Building: Users helping each other, sharing solutions Distributed Load: Community built local simulators (like we did)